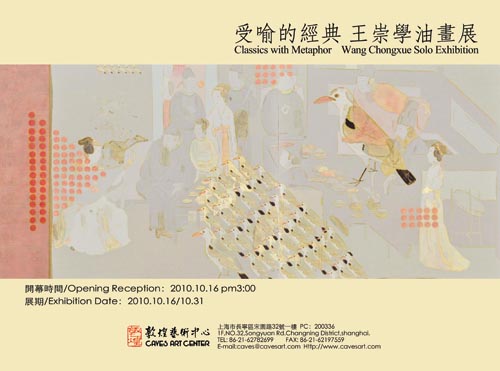

展览时间:2010-10-16 ~ 2010-10-31

展览地点:上海敦煌艺术中心

特邀批评:彭肜

参展艺术家:王崇学

开幕酒会:2010-10-16 15:00

展览介绍:

经典如何当代化和现在化,即如何让历史性的历史经典在解构主义盛行的今天获得它存在的意义与价值。而王崇学的高明之处就在于他借用了当代性很强的“透”技法重新赋予了经典作品的当代价值。

我将王崇学的艺术语言称为“透技法”。在他的画中,层层叠叠的图像、色彩、颜料与笔触相互“渗透”、“穿透”和“通透”,使画面层次极为丰富、厚重而显得灵透,避免了呆板和笨拙。除此之外,“透技法”的深层语法功能在于多重后现代美学技巧的相互交织与“渗透”。在画面最底部,他以“点”进行“复制”,难以计数的“点”构成了作品丰富的色彩层次与扎实的技术品格。同时,“点”与“点”之间的疏松的距离又很好地“透”出画布的底色与质地。进而形成“绢”的质地,产生了具有时间性的“物质感”。黄荃画中的鸟与花,被王崇学在画面上极工整而有规律地重复排列起来,悬置在画面中的某个位置,整齐而突兀。在鸟与花的底部,顾闳中的《韩熙载夜宴图》被后现代式地截取和“拼贴”起来——“透”过黄荃的花与鸟的图像我们真切地看到了顾闳中的韩熙载夜宴图。无论是黄荃还是顾闳中,其艺术的视觉图像都被强行“挪用”,从中国传统美术特定的时代语义场中移入到杂乱无章的当代艺术领域当中。被“挪用”的传统因而丧失了其内在的文化内涵与美学意蕴,而它们之间所衍生出来的某种指示和互文关系又使画面异常丰富和神秘。 王崇学以一种独特的图像修辞学将中国传统视觉经典图像在当代消费语境中复活了。我由此认为这正是他对当代艺术的一个贡献与创造。他给出了经典进入今天这个时代的路径与通道,他以一种很有蛊惑力的方式保存了传统经典的魅力与价值。与许多当代艺术家不同,王崇学崇敬经典,他没有采取一种痞子般的戏谑态度来嘲弄、嬉戏、颠覆与解构经典,而是以一种建构性的后现代艺术语汇来正面地书写与“透视”经典。经过他的“透技法”处理,艺术传统与经典图像获得了重新进入当代艺术空间的可能性与现实性。

王崇学在这里显示出了他的创造性,他在汲取了后现代美学话语的时候抛弃了其轻佻与虚无的一面,成功地完成了与经典的对话,复活了中国传统艺术的视觉美感,让我们“透”过长长的日子回望到了遥远的过去和久远的历史,也因此,他为中国当代艺术提供了一条传统经典当代化的艺术之路。

彭肜

Metaphor Interpretation of the Classics

---A Reading of the “Penetration” Series of Wang Chongxue’s Oil Painting

Peng Rong

When I first came across Wang Chongxue’s paintings, the feelings of gentleness, tranquility, purity and aestheticism provoked by them were the same as those provoked by my first experience of getting in contact with him in person, nothing very “mysterious”. Yet what was unusual was, after I left his studio and looked back, there seemed to be some “secrets” in his paintings, which were unspeakable in terms of their depth of meaning as well as flavor of culture.

From the subjects of his paintings, we can see that they are very simple and plain. For many years he has been reviewing and pondering repeatedly traditional Chinese art classics on the frames. In his works, the image of “birds” from “Rare Birds Sketched from Nature” (Xiesheng zhenqin tu) by Huang Quan, a flower-and-bird painter from Five Dynasties (907-960), have been relocated on the frames of “Painting of Han Xi-zai's Evening Banquet” by the figure painter Gu Hongzhong. This relocation enables the traditional classical art images to reflect an amazing modern beauty. From those frames, what can be easily felt is the distance daubed by the lapse of time. The birds from Huang Quan’s painting are still full of life, the flowers blooming, and we can still feel the hangover from Han Xi-zai’s banquet and hear the careladen sigh of Li Yu, the last emperor in the Later Tang Dynasty (923-936). And the ground of the paintings, which is with segistration of gray and yellow and reminds people of the dusk when it becomes dark and evening mist is gathering, also attempts to enwrap us in the imagination and the atmosphere created in the Chinese verse “life can not always compensate for the regret, as is always the river to the east”. However, we can tell that it is not Wang Chongxue’s intention to let his viewers express their reminiscence of the ancient times in front of his paintings. Those ancient narratives have long solidified and turned eternal, though their stories remain breath-taking forever in their eras called the past. Now that they have become typal signs and images sculpted by time, they are easily arranged and lined up at his option.

This was my first impression on Wang Chongxue’s oil paintings. The poetic flavor and refinement of traditional classical paintings are filtrated and recomposed by the contemporary visual experience, without the original decadent and corrupt tinge, and a new aesthetic order is self-evident in the desolate frames. Obviously this kind of perception fit my habitual aesthetic ideal and also succeeded in winning me instantly. But I felt somehow it was not quite satisfactory, since this level of reading his paintings seemed too careless. And some more rich connotations and revelations are still yet to be brought to light. After reading and contemplating the frames time and time again, I finally realized that the theme of Wang Chongxue’s art should be the “metaphoric interpretation of the classics”, or more accurately “the metaphoric re-interpretation of the classics”. This process includes two levels, the first level is to revive and modernize the classics; the second level is to give meaning to the classics in the new time context over again, thus enable them to have new “meanings”. The ability to combine these two levels of meanings together skillfully and organically might be the “secret” or “depth” that I perceived in Wang Chongxue’s paintings. Through giving meanings to the classics again, Wang Chongxue builds up a secret passage from where sets out in the ancient times and enters the modern times. By doing so, he also endows the frames their own growing logic, hence a unique interpretation and cognition of the traditional and the classics.

The reason why the classics are classical is that they are the traditional remains with the attributes of time and history. The time elapsed and the repeated reading that has withstood the test of time is a vital added value to the classics. But today, the classics seem to become the victim of deconstruction overnight. This is especially true when we enter a new century facing rapid changes—various kinds of cultures, information, new technology and new lifestyles which exist everywhere always affect and influence us. Everyone is chasing, losing and drifting among the fashionable trends and multiculture with perplexity. The fate facing the classical and traditional is either to be appropriated as the postmodern ornament or to be forgotten without any trouble. The rapidity of it can be perceived from a Chinese verse “The flowers in the woods have rinsed off colors, too too rushed” . Needless to say, “Painting of Han Xi-zai's Evening Banquet” by Gu Hongzhong and “Rare Birds Sketched from Nature” (Xiesheng zhenqin tu) by Huang Quan, as the classics in the history of Chinese fine arts, are indeed far away from us with a span of over one thousand years. Choosing such subjects, apart from the reason that he is full of nostalgia for the classics and filled with tribute to the traditional, he is also doing his best to bring the classics back to life by a modern means of modern art. Maybe at a time when everything is more and more materialized and technified, the traditional and the classics, to some extent, can only remain to be the strongly drifting homesick of the artists. The land is still the land, and the moon is still the same, whereas we have been displaced in our own cultural tradition and classics, with an intense homesick and yet homeless. What a profound message it conveys!

That how to turn the classics to be modern and present, or how to enable the historical classics to reclaim its meaning of existence and value in this era when deconstruction is prevailing, has become a historical mission that should be undertaken by the contemporary Chinese artists. At the same time it has also become an artistic gateway leading to success. The brilliance of Wang Chongxue lies in that he borrows the modern “penetrative” technique to rejuvenate the classical paintings with a modern value.

The reason I call Wang Chongxue’s artistic language “the penetrative technique” is because it combines three postmodern aesthetic techniques in a secret way: “mechanography”, “collage” and “appropriation of the tradition”. The seeming syntax of “the penetrative technique” is “penetration”: penetration of the colour, penetration of the ground and penetration of the trace. The artist has long had a detailed explanation and a profound description, which saves me the trouble of spending more time on this. In his paintings, different images, colours, pigments and strokes interpenetrate, penetrate and permeated through each other tier upon tier, producing a multilayer effect which is at the same time heavy and light without inflexibility and clumsiness. Besides, the syntax function of “the penetrative technique” on a deeper level is reflected in the mutual interweaving and “infiltration” of multilayer modern aesthetic devices. In his book Art Works in the Mechanical Reproductive Era, Walter Benjamin brings up a very sophisticated term “duplication”, which is also a key threshold to understand Wang Chongxue’s implementation of “the penetrative technique” in his oil paintings. “Duplication” is what Wang Chongxue does well in. At the bottommost of the frames, he applies “dots” to “duplicate” what he wants. Countless “dots” have constructed a series of rich colour layers of the works and the solid technical character. At the same time, the loose connection between dots also makes the ground of the canvas “penetrable”, generating the texture of “thin silk” and therefore “a material sense” with timeliness. Adopting the device of “duplication”, Wang Chongxue adds more richness and weight to “the penetrative technique”. The objects of “duplication” are firstly the flowers and birds in Huang Quan’s painting. They have been allocated somewhere in the frames, in a extremely neat and regular manner, giving people the feeling of order yet unexpectedness. At the bottom of the flowers and the birds, “Painting of Han Xi-zai's Evening Banquet” by Gu Hongzhong is intercepted and pasted up in a postmodern manner. If we ask what is the logic between the images in Huang Quan’s paintings and those in Gu Hongzhong’s, we cannot find the answer from ordinary artistic language and imaginal thinking theories. Yet it can be explained from the perspective of postmodern aesthetics. There is no cultural logic or meaningful connection between these two subjects. If we must find out some sort of connection between them, then it is “collage”: place completely irrelevant images randomly together, producing an illogical yet peculiar beauty. From the terms of “the penetrative technique” employed by Wang Chongxue we can see “collage” means “penetration”—“penetrating through” the images of flowers and birds in Huang Quan’s painting we can perceive those in “Painting of Han Xi-zai's Evening Banquet” by Gu Hongzhong. And that is it, nothing more. If we look at them in terms of the subject, we will be able to find the third modern feature of “the penetrative technique”: “appropriation of the tradition”. For both Huang Quan and Gu Hongzhong, their artistic visual images have been appropriated by force. They have been transplanted from the special temporal semantic context of traditional Chinese fine arts to the disordered and unsystematic realm of modern art. Hence the traditional which was “appropriated” has lost its own cultural connotations and aesthetic implications, and certain indication and intertextuality generated by this appropriation greatly enrich and mystify the frames.

Based on the comprehensive application of the three basic kinds of postmodern aesthetic syntax: “mechanography”, “collage” and “appropriation of the tradition”, Wang Chongxue revives traditional Chinese classic visual images in the modern consumer context with a unique rhetorics of the images. Therefore I recognize this as his contribution and creation to modern art. He presents us a gateway and passage for the classics to enter the present, preserving the charms and values of the traditional classics in a bewitching manner.

Unlike many contemporary artists, Wang Chongxue honours the classics. Instead of ridiculing, larking, subverting and deconstructing the classics in a playful way as a ruffian, he positively writes about and “perceives” the classics with a set of constructive postmodern artistic vocabulary. Thanks to his “penetrative technique”, artistic tradition and the classical images gain the possibility and feasibility of re-entering the contemporary artistic space. In Wang Chongxue’s paintings, the rejuvenized classics seem familiar and strange at the same time. They are no longer timeworn, rotten and backward, but full of vitality and other sense of beauty. In the Chinese artistic history of the new era, apart from the deconstructive cynicism on the tradition, there is also other ways of carrying on the tradition by following the doctrine of “back to the ancients”. However, if this is what we only can do to represent the classics, it can justly prove our mediocrity and inability, for any slogan or method of “making the past serve the present” and passing on the cultural heritage has become prevalent custom and therefore has little effect, basically unacceptable by the people and the time.

Wang Chongxue reveals his creativity by borrowing the postmodern aesthetic discourse while disposing its frivolity and airiness. In doing so, he successfully completes a dialogue with the classics and revives the visual aesthetic sense of the traditional Chinese art, enabling us to “penetrate” the long years to review the distant past and agelong history. Because of this, he has provided the Chinese modern art with an artistic way through which the traditional and the classics can become modernized.

The secrets of Wang Chongxue’s oil paintings do not simply lie in the “revival of the classics”. Revival means rebirth, and rebirth indicates a previous death. Obviously, before reviving the classics Wang Chongxue has “murdered” the classics. Only through murdering the classics in the first place can he re-arouse the classics in a magically manner. His murder of the classics is again completed through his postmodern “penetrative technique”. In analyzing modern phenomena, the postmodern aesthete Jean Baudrillard used the term “simulacrum”. From his perspective, the major difference between the modern culture and the traditional culture is the former one is full of huge amount of vivid signs and images through artificial virtualization. He called these signs and images “simulacrum”. On the one hand, as “copies” and “duplicates”, “simulacrum” resembles the “original” closely, to the degree that it can even replace the “original”. But on the other hand, “simulacrum” has the attribute of artificial virtualization, therefore it’s only a “copy” rather than the reality. Through a virtual yet “real” way “simulacrum” completes the “murder of reality”. Baudrillard had a quite profound analysis towards this, which is almost applicable to Wang Chongxue’s oil paintings.

On Wang Chongxue’s part, he “appropriates” the classical images from both Gu Hongzhong and Huang Quan’s paintings from the Chinese history of fine arts. By “duplicating” and “pasting them up”, he further produces a multilayer “penetrative” linguistic relationship, thus dissevers the connection between the classical works and time context, emptying the semantic connotations and the aesthetic implications of the classical images and undoing the narration and meaning in the original frames. In fact, in Wang Chongxue’s paintings, we cannot have felt the vigilance of Li Yu, the last emperor, the peeking of Gu Hongzhong and Han Xi-zai’s resignation and craftiness behind his fictitious wallowing in sensual pleasure, which were all revealed in the original “Painting of Han Xi-zai's Evening Banquet”. In his discussion about the features of “mechanography” in modern art, he points out that the application of the industrial way of “duplication” popularizes the classics of art, making art accessible to the common people. Yet, it also brings tremendous harm to the classical works –the “spirit” of the original classical art is lost during the process. No doubt, Wang Chongxue also empties the connotations of the original works as well as loses the “spirit” of the classics when he duplicates, appropriates and pastes up the classics. But the incredible thing is after murdering the classics Wang Chongxue is able to giving some brand new “connotative meanings” back to the classics. Thus comes a fantastic situation—in Wang Chongxue’s paintings, the classics are floating on the frames like a bunch of “emancipated symbols” (Baudrillard), which are “permeating” and “penetrating” through each other, receiving their new “metaphorical interpretation” larkishly with free will. They no longer passively convey the cultural connotations and aesthetic implications of the traditional classical texts. They seem to be losing while also gaining something, dying as well as living. They are full of vibrancy. The opening of the multidimensional “metaphorical meanings” is continously producing various interpretations with a surprising aesthetic flavor.

Maybe it is until now when we find out the seemingly simple oil paintings of Wang Chongxue are not simple at all, for it contains so many layers of meanings. Just like the name of the paintings—“penetration”, these layers of meanings overlap with the classical images in a “penetrative” manner, with rich and ample connotations. They are based on the present era to revive the tradition, with an effort to give a completely new “metaphorical interpretation” to the classics. I think, that is enough to enable us to see the secrets behind the frames of Wang Chongxue’s paintings.

By the Jinjiang Riverside in Chengdu, June 2008

- 2011-04-30 ~ 2011-05-30出窍记·缪晓春个展

- 2011-04-29 ~ 2011-05-20静中人Figures of Silence —Michel Madore

- 2011-04-30 ~ 2011-05-14黑白

- 2011-05-28 ~ 2011-07-28四重奏——孟昌明水墨荷花作品展

- 2011-05-28 ~ 2011-06-24“远与近”意大利当代著名艺术家作品展

- 2011-05-28 ~ 2011-07-02底下有石头:杨心广个展

- 2011-05-21 ~ 2011-06-20湖滨诗境──Celest生态摄影展(续展)

- 2011-05-21 ~ 2011-06-05缓行——十二位八零后艺术家

- 2011-04-28 ~ 2011-06-05观天悟道——张国龙艺术巡展

- 2011-05-28 ~ 2011-07-10诺特·维塔尔:激浸